« Baseball Season is Over. Goddamn Winter has Officially Come | 回到主頁面 | The Demise of Vinyl? Not Even Close »

2005-10-28, 5:57 PM

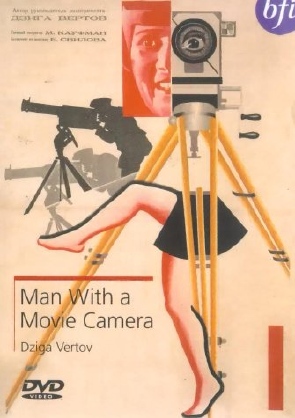

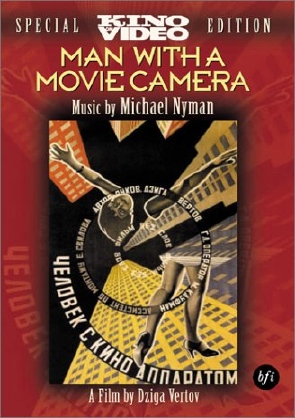

The Man with a Movie Camera by Dziga Vertov

Denis Abramovich Kaufman, adopted the pseudonym Dziga Vertov, which means “turning & revolving”, is one of the greatest documentary filmmakers in Russian history. He was a medical student at his college life in St. Petersburg, and highly enthused over the futurist poetry and sound collages. For exploring all possibilities of aural world, he established an audio laboratory in his early twenty.

In his incipient career, he became the editor in the Moscow Cinema Committee for Kino-Nedelia, which was the first newsreel series in Russia appearing from June 1918. He met his wife Elizaveta Svilova there as well, who subsequently edited most of Vertov’s films. He worked on film weekly series for three years; during this wartime, his mission was to collect incoming fragments of films: chaos, disasters, famines and struggles, then reorganizing and subtitling them into a meaningful way, and distributed them back to the battle frontline for being seen by Russian troops.

During his stay in the Cinema Committee, Vertov compiled a wide range of newsreel footages for making the documentary releases like Anniversary of the Revolution (1919) and History of the Civil War (1921). But his most significant contribution to documentary genre, and the hugest impact on Russian film industry wouldn’t happen until he built the Council of Three in 1922. This group’s “three” represented Vertov, his wife and his brother Mikhail Kaufman, who was also a cinematographer and filmmaker.

They began an ambitious project called Kino-Pravda (Film Truth), which carried a stubborn belief that filmmaker should give up the traditional narrative approach for making dramatic fictions, but to capture the daily actualities which were easily ignored by average people. By organizing and arranging these fragments, filmmaker could show a more authentic truth that couldn’t be seen with naked eye.

Over a period of three years, twenty-three issues of this series were produced and each one usually covered three different topics such as traffic in the city, children in the hospital and other daily routines that happened in factories, schools and marketplaces, and these short films at least lasted for twenty minutes. Throughout these practical experiences and sufficient preparations, Vertov finally made his masterpiece, The Man with a Movie Camera in 1929, regarded by many critics as on of the most innovative precursors of the Avant Garde genre. I will discuss this film’s achievements in the following aspects.

1. A synthesis of his theories about film.

Vertov’s main theory about filming is the “Kino” style, which could be Kino-seeing (I see through the camera), Kino-writing (I write on film with the camera) and Kino-organizing (I edit the film that was made by the camera). In other words, by systematically recording the everyday experiences and documenting the daily facts, the Kino methods are director’s experimental ways of investigating the real world.

Kino-eye is not only an artistic movement, but also a revolutionary concept that has potentials to redefine the way that people have seen and been seen through the medium of the film. By massively using montage skill, which may probably one the most essential components in Kino-editing, director can adopt a large amount of post-production techniques, like reverse action, animation, acceleration and still-framing to re-create a surreal dimension which would bring some kinds of ecstatic experiences to its audience. Hence, this extraordinary approach conquers both time and space. To some extent, it wrenches and twists the normal way people perceive its surroundings and environments.

For Vertov, montage means writing something cinematically with the documented shots. Every Kino production has its own theme and is subject to montage. For more specifically, to complete a montage process, there have three stages to achieve. Firstly, classifying data. Editing is like to classify all kinds of data that has been selected and collected throughout the filming process, like photographs, newspapers, manuscripts and documentary clips. These data may direct or indirect related to the original theme, thus by doing so, filmmaker can filter and group them into the valuable fragments, and the theme will gradually become more incisive by this procedure. Secondly, observing and selecting. By selecting specific segments during the editing process, director can sum up the observations that were previously made by the camera, so-called machine eye.

Finally, seeing is believing. The montage brings the combination of addition, subtraction, mixings and shifts altogether; all these contradictory elements have been melted into a hot pot, like a kaleidoscope, where all pieces are arranged in a rhythmical pace and placed into a mechanical order. Movement between shots is according to Kino-eye, which constructs an inner establishment like the visual formula and equation. The result of seeing the Kino film is audience will be attracted by its opulent editing skills and persuasive intentions; therefore may more easily to believe what they’ve just seen.

In short, Kino-eye is the possibility of seeing normal life at any momentum or in any material order that is inaccessible to the unaided human eye. In The Man with a Movie Camera, Vertov used all these kinds of Kino tactics to decode the originally invisible world. Furthermore, though the initial version didn’t come with the score, following Vertov’s instructions, The Alloy Orchestra composed a post-modern oriented soundtrack for this film in 1996. If we delve deeper, we will find besides Kino-eye, Vertov also advocated the concept of Radio-eye, which means audible Kino-eye transmitted by radio. Its purpose was to eliminate the distance between people. During that silent era, Vertov had already been aware of the power of sounds; he was really acting like a prophet.

2. A document about daily life in the revolutionary city.

In 1929, Russia was in a fluent state, whether its culture, economic, politic and technology was filled with uncertainty. It had lagged behind the Western world’s Industrial Revolution, though it followed tightly, no one really knew what the end result would be. So this kind of insecure but sometimes enthusiastic atmosphere in its capitol Moscow was exactly what Vertov tried to convey in this film.

Through the use of new machinery, the Russian farmers could manufacture more efficiently and workmen would able to produce in greater numbers. These laboring processes, including other daily activities from mundane rituals like weddings, funerals and divorce registrations, to other social exercises like ballgames, swimming and diving, were all highlighted in The Man with a Movie Camera.

Vertov created a vivid portrait of the city of Moscow as a typical day went by. He focused on everyday experiences and successfully captured the vibration of a stupendous city. In addition to its artistic accomplishments, probably the most important part of its success is The Man with a Movie Camera unassumingly generates an optimistic attitude against the unwritten future.

3. A paean of praise to the documentary cameraman and editor.

In Erik Barnouw’s book, his thought about The Man with a Movie Camera is “We see the making of a film and at the same time the film that is being made”. It’s the precise explanation of the relationship between film itself, its cameraman and its audience. The cameraman we saw in this film is Vertov’s brother Mikhail Kaufman, who took its arduous mission by using complicated organized and technical operations. Besides, he invented several new pieces of apparatus for his camera and created lots of innovative special effects for making this provocative film.

Charging the camera, Kaufman not just dealt with the technical stuff, but captured some really impressively poetic images and remarkable sequences. He was sensitively aware of the distinction that could be made by setting the camera in different locations, positions and angles. Sometimes he shot with a hidden camera without carrying the permission, so we could safely say Vertov’s thoughtful theory and Kaufman’s courageous execution made this film an undeniable classic. In addition to Kaufman’s conspicuous appearance throughout the film, its editor also appeared in some sequences, by these chances, this film made a modest tribute to its makers.

4. A complex essay on the nature of film truth.

The Man with a Movie Camera denied all rules set up by the previous filming standards. It renounced film studios, actors, scripts and sets, thus was completely separated from the conventional theater and literature. It created a never-seen-before cinematic language that challenged human eyes and broke all linkages between the existing constructions. It was so eager to bring its truth to audience, but simultaneously, via the overwhelming usages of montage and editing skills, it also built a dangerous fakery.

There is a profound metaphor in The Man with a Movie Camera. Seemingly Vertov wanted people aware of the weakness of their eyes, so he used machine to record the daily details and reproduced them by cinematic methods. But it also makes us to ask a question: If what we see by our eyes isn’t the truth at all, why do we believe what we see by the camera? If the montage can easily manipulate the original footage, why can it be more real than the scene we just saw under its natural status?

Vertov hoped people could ponder all kinds of facets whether it’s film truth or reality truth. And his legacy has still ruled the Avane Garde genre. After half a century later, we can see lots of similarities and resemblances in Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi, and Vertov’s influences continue.

[電 影] 引用(0)

引用

迴響

「至於Cinéma vérité則完全是另外一回事了。紀錄片導演透過事先安排好的橋段或情節,讓電影看起來”更趨近於真實”,即使它的本質是不真實的。」

這種似是而非的胡說八道,不知道是那邊抄來的,真是令人嘆為觀止。

真實電影是在承認拍攝者存在,且可能多少會介入並影響拍攝客體的前提下

拍攝者如何藉由主動介入被攝者,來挖掘出全然被動的狀況下可能拍攝不出的真實

這跟你講的導演事先安排橋段,讓電影看起來更趨近於真實,完全是天馬牛不相干的兩回事

抄網路資料也應該要多查證點吧,唉

由 持大聲公的人 發表於 February 20, 2006 9:43 PM

「即使它的本質是不真實的」這句話更是好笑

真實電影是用有別於直接電影的哲學觀,去發掘所謂的真實

什麼叫做「即使它的本質是不真實的」,真是好笑。

由 持大聲公的人 發表於 February 20, 2006 9:47 PM